A lot of game stores make their money from Magic singles. They're undeniably a major part of the game store ecosystem. They aren't without their trade offs and problems. I've sold Magic singles in store for about as long as I've not sold Magic singles. I don't sell them any longer. I don't think we were particularly good at selling them, mostly because we were perpetually under capitalized. Here's my list of why they're a problem:

Required Knowledge: The product and trade knowledge required to properly sell singles is dramatic. I don't believe there is any other store trade where required knowledge is so extensive. It can be all consuming. If you come to the trade as an experienced Magic player, you likely think you have skills to run a store, solely on your Magic knowledge.

If you aren't a Magic player, you will have a hard time not only learning the meta of the game, but you'll need to keep up with new information on a continual basis. Even quarterly set knowledge is not enough. You'll need to be plugged in daily.

This is also a problem because you may like Magic now, but you probably won't forever. After 17 years, I've seen all of our judges and knowledgable employees get burned out with Magic. I would not want my business tied to my enthusiasm over a product. That's exactly what happens in this trade.

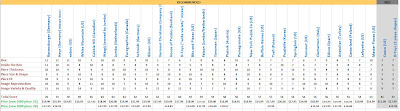

Time Investment: Besides keeping up on product knowledge, there is considerable time in buying, sorting, re-pricing, and engaging with Magic singles customers, many of whom are not looking to spend a lot of money. There are a ton of low value purchasers, many of whom come to your store to talk with you about Magic. This is their entertainment, but if this isn't your primary trade, it's not a good use of your time. They will reward you with their money for sure, but this is a rabbit hole that you are stuck in. There are a lot of more useful things you could be doing with your time.

Eventually this time cost is delegated to employees, who you now pay by the hour to buy, sort, organize, and price cards, as well as jabber with Magic players. In high wage states, this becomes even more untenable. $15+ an hour is a lot of money to shuffle cardboard. The same activities might be happening a mile away over the border, at $7.25/hour, and the singles market is mostly online, where you could be paying up to 15% for the opportunity to sell.

Capital Investment: It's hard to dabble in Magic singles. The cliche is the store owner who starts their store with a binder and folding tables, but that binder could be a significant capital investment in this trade. I stopped selling singles, but if I got back into it, I would want to ear mark tens of thousands of dollars to build a collection. $50K sounds like a reasonable start. There are a lot of easier ways to invest $50K. Attempting to bootstrap Magic singles is very difficult, and unlike product that can be bought from supplier, you'll likely seed your start up by opening a lot of booster cases with low resale margins.

Cash Flow Nightmare. Magic singles will mess up your cash flow, if you aren't well capitalized. Don't be surprised when you have a great sales day, only to discover there are no deposits because you had to buy a collection or replenish your cash on hand. You can't really control when this will happen. You can't buy singles this week and not next week because you don't have money for payroll. You can't buy product and promise to send a check when you get around to it (that happened around here). During the pandemic, we sold all our singles during lockdown and as organized play died, stores that did a lot of singles business were forced to decide if they wanted to continue to buy a product that nobody, temporarily, wanted. When we dropped singles, our cash flow went from a nightmare to a dream.

Potential Theft and Fraud: Magic singles are essentially a cash business. In the infamous Gaming Goat deposition, we have the claim that Magic singles, seven million of them, have no value: "It doesn't have a value. It's cardboard." We need to work on these quotes. Along with "No, I am your father," it may be the most mis quoted phrase amongst my trade peers.

Hopefully you understand that Magic singles are valuable inventory, easy to price, and taxable as inventory and compensation when applicable. You can't pay people in singles and expect that not to be taxable income. My guess is a lot of stores don't declare their singles as part of their inventory and some probably pay their sorters in product.

Singles are easy for employees to steal and self deal, for store owners to use to evade taxes, and they're likely not properly insured. I once discovered an employee was living under a gaming table, sleeping in the store. He made his food money by stealing singles from the case and selling them back to us. It was like supporting a child that wasn't mine. It's also common for employees to be customers, and when your Magic buyer is also a Magic seller, you need to make sure a third party is monitoring sales. Putting limits on the number of each card you'll keep on hand is a good start.

Do you 100% trust your employees to handle your Magic singles? Can you or should you trust them 100%? If your knowledge is lacking or your enthusiasm waning, you will have to trust your employees to handle this part of your business without much ability for oversight. I am aware when standard product is sold, missing, or otherwise being mishandled. I can feel it in The Force. I had no idea what was happening with my singles.

Insurance is another issue. When we had a lot of Magic singles, we had them insured as "fine art," They weren't considered part of inventory like other product, despite their obvious value. How often do you think I adjusted the value of my "fine art" policy rider?

The solution is specialized tools for selling Magic singles, which begins to dominate the focus of your business. You'll end up choosing a point of sale system based on its ability to track singles and integrate with online marketplaces. This seems a lot like the tail wagging the dog, especially if singles don't dominate your sales.

Margin Justification: Sealed product margins are crap. Since we don't have an MSRP any longer, not that this mattered, I'm basing this on market prices. Magic is a commodity good, it's no better at my store than the store in the next state over. Customers shop entirely on price. Sealed Magic margins are 30-35%, in a trade that regularly gets 40-45%. Stores make up for this with singles.

Singles make Magic profitable. When I sold them, we tended to get a 50% margin, at least with what we bought and sold, ignoring the ocean of crap that would only sell in bulk. It does work, if you do the work and make the investment. Singles make up for the sins of sealed commodity Magic. If you sell sealed Magic and don't sell singles, it's kind of a suckers game. You're not losing money, but you're relying on volume to justify the low margin. You might get stratospheric turn rates, if you're careful. But as you try to be the local Magic store by keeping older sets in stock, you'll find your turns begin to decline sharply, as you keep slow selling product in reserve. I'm doing this right now.

Perhaps you hold the line at a higher margin, knowing you'll sell a lot less of it. I've tried both approaches for years at a time, and market pricing Magic seems to work best. It also makes up for the fact I don't sell singles. High prices and no singles would mean Magic customers only come to us because we're a good play venue. Don't forget the second part of the game store cliche, a bunch of folding tables.

Singles are integral to propping up this de-valued product and the meta is carefully managed to maintain long term values. This feeds back into requiring the store owner to once again have a high level of Magic knowledge, with huge time investments, and plenty of capital on hand, preferably rolls of cash in a safe on site. This is not a situation you can manage remotely. It's not the kind of business you can easily sell or retire from, unless you can find another Magic expert like you've become. Magic singles are golden handcuffs, tying you to not only Wizards of the Coast, but to your store counter for life.

Anyway, one mans opinion.

You can make a ton of money selling Magic singles and I love it as a game.